How Some Designers Create Bad Clients

Some words of advice to young designers on what their clients want to see.

I’m not a designer myself, but as a middle man, I have worked with my fair share of them, and I’ve seen endless frustration in their meetings with clients.

While those clients certainly bear their share of the blame, it’s ultimately the designer – brought in to be the expert advisor in the situation – who’s responsible for managing the design process and getting to a result everyone is happy with.

The client comes to the table with expectations, which may or may not be reasonable, but from the moment they delegate the work, they can really only respond to what you, the designer, gives them back.

So if you’re a designer and don’t like the response you get, you should at least consider how you, yourself, may have been complicit. What did you put forward to elicit that response?

Ask more, better questions

In my experience, the biggest and most mistake young designers make, is to ask the wrong questions – either explicitly, or implicitly.

Remember: Clients want expertise.

They hire specialists like you, because they want to work with people who know what to do and how to do it. So what does that look like?

Expertise shows up as curiosity and humility around questions of purpose and identity, but as confidence and decisiveness around the art and craft.

Too many inexperienced designers (and quite a few who should know better) don’t ask enough questions, or the right questions, about their clients’ goals and their area of expertise. They don’t fully understand or respect the objectives or the challenge of the design, the subtler parts of the message, the conflicts that need to be solved, and how to think about the trade-offs that haven’t yet been made.

Worse: They don’t even realize what they don’t understand.

Instead of asking questions, they work with too little input, based mostly on their own unfounded assumptions and personal preferences. Good design requires insight. Without it, your design will fail to impress the client.

Act as an expert, not a student

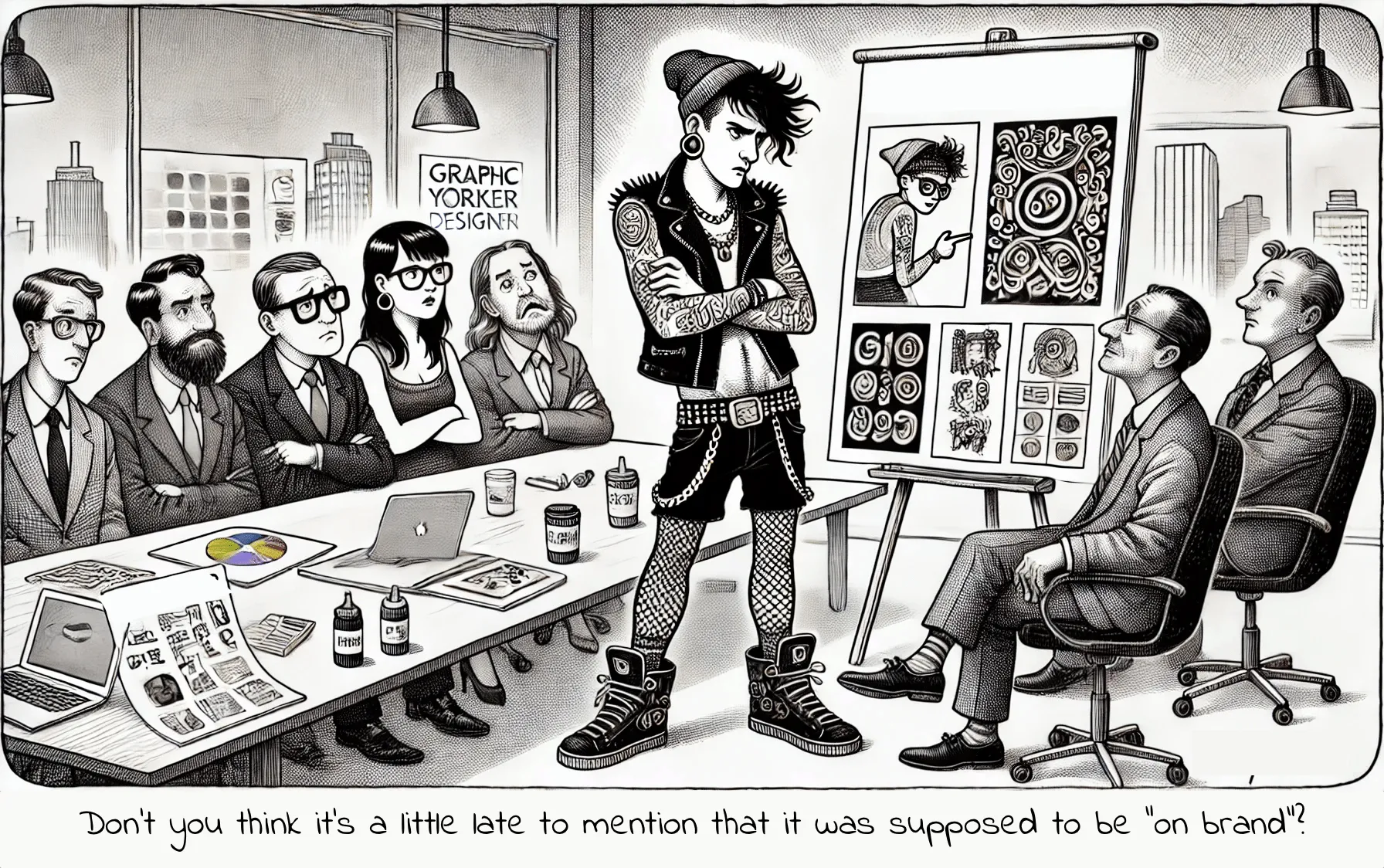

Then the designer returns with a bunch of unimpressive first drafts or sketches — many different options, which differ with regard to usage of fonts and colors, the size and position of the logos and the shape of the button.

And they present them to the client, as if the client is their teacher, and should tell them what’s good and what’s not. (Hint: They’re not. If you need a mentor, get one, but don’t put that on your client.)

Or worse–and this is how the client often interprets it–as if the difference is a question of taste, rather than function. As if no option is better than the others on any dimension, except subjectively.

“Which do you like better?”

When you do that, you’re asking your client to have an opinion on issues that are squarely within your own area of expertise, and you’re communicating that you don’t know any more than they do.

It’s not the client’s job to choose between fonts or have a vague preference for a particular layout. You’re making the client uncertain.

It’s like the surgeon asking the patient whether she should go in through the thigh or the abdomen. If the surgeon understood the diagnosis, she should know. Even if both options might work, one person is more qualified to simply make a decision than the other.

But the client wants decisiveness, so they will be happy to make a decision if you don’t. If you ask your client about button size and color gradients, don’t be surprised if they start micromanaging you.

That typically leads to indecision, delays, confusion and regret, and worse designs and less happy clients.

Design like it matters

The alternative is to present the client with different drafts and sketches that go in very different directions, because they prioritize the client’s wants and needs differently. They represent opposing strategies for tackling the client’s challenges, that might even go to the core of their identity.

This changes the question from “which do you like?” to something like “what is more important?” or even “who are you … really?”.

It shows that you understand what the client wants done, and you’re confident in your own ability to do it, but you are open to learning from the client about what they know best – their own business and priorities.

Of course, the client will still have an opinion on the size of the logo and the shade of blue you have chosen, but now you have a better framework for dealing with that input.

If it makes a difference for the purpose of the design, you can explain that with the authority of someone who acts and speaks as if design choices really matter – and not as someone who’s always looking to the client for the right answers.

And if you know it won’t make a big difference, you can say that, and still give the client what they want without sacrificing an iota of pride in your work.

Rules of thumb

Here, then, are my rules of thumb for designers interacting with clients:

- Always trust your own expertise, taste and style, while also listening respectfully to the client–especially on their area of expertise.

- Never give your client too many options. For simple tasks and clients you know well, one first draft may be enough. Otherwise, two different directions should do. Sometimes you need to show a third way, or a synthesis of the two others, but never show more than three. If you need more, you haven’t asked enough questions. Pick up the phone.

- When you provide options, make them significantly different. Not just different text alignment, a few centimeters change in position, or 4 pt larger font size. Change the entire idea, including the copy, purpose and function of the design. Force the client to consider the big, important questions: “What is the purpose of this?” and “Who am I?”, not small questions, like “should this be less pink?”

- When you have a strong preference about what the best option is, don’t provide other (necessarily worse) options. Instead, question your assumptions, and make better alternatives, until your preference is no longer quite so strong.

- When you don’t have a strong opinion, make a decision anyway. That’s part of the job. But don’t try too hard to defend it if your client doesn’t like it. Instead, ask and listen to what the client says, so you learn how to make the decision the next time.

- Listen to the client, even when you think (know?) you are right. The client may be off about design and solutions, but they are usually right about their feelings and objectives. If they think something is wrong, it probably is – just not necessarily what they think it is.

- Prepare to defend your big choices, and your core idea, but don’t spend any time or energy defending choices you don’t actually care about. (Sounds obvious, but pride has a way of picking unnecessary fights.) The better your core idea and execution, the easier this gets.

- It is always possible to edit more, so never be surprised or disappointed if you are asked to make another change. Consequently: Never, ever name a file “final version”, because it almost never is. And never ask for opinions on work you consider finished, because you will get them.

- When you think you’re finished, don’t ask. Let people know: “This looks really good now. I think we’re done.”